Chapter 6 – Likes and dislikes

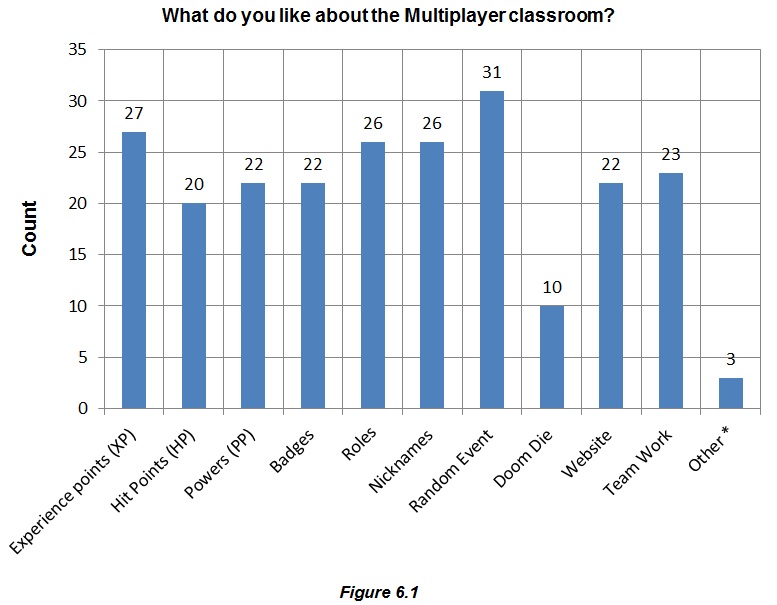

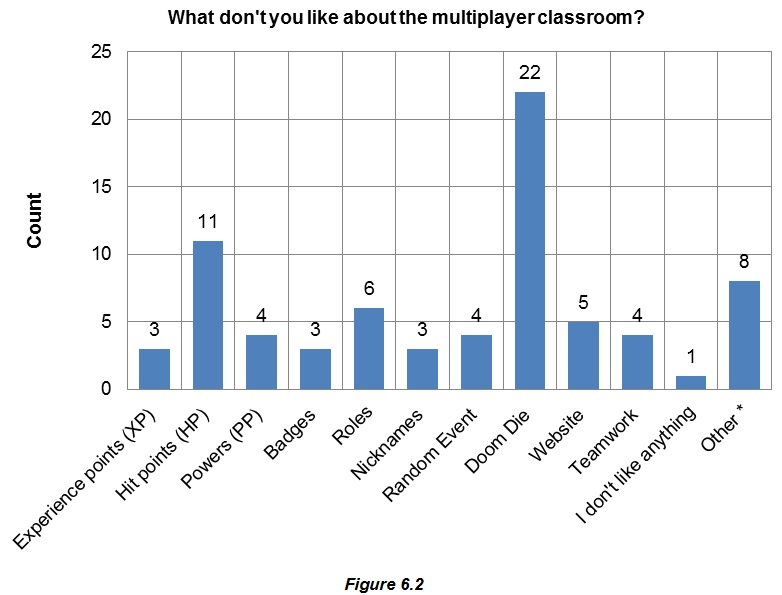

Figure 6.1 and 6.2 represent the MG responses to two of the questions in the final questionnaire. Students could choose more than one item from the list of multiplayer classroom features. These features are then discussed in more detail below.

| Contents

Likes and dislikes 2 Powers 3 Badges 6 Doom die 7 Profiles, website and levelling up 8 Teamwork |

*See Appendix 8.1 for ‘Other’

*See Appendix 8.2 for ‘Other’

XP and HP

The use of incremental rewards appeared to be popular and appreciated (Table 6.1 and 6.2). Gee (2007) says that players observing their progress through a game can ‘repair’ damaged self-esteem and build confidence. In week7 Evra seemed disappointed when he said, “No XP today” as he had not completed the whole activity, and was visibly pleased when I pointed out that on the instruction sheet it said how much XP they would receive per item and he would receive XP for the tasks he had completed. In week8, some students in MG2 were pleased to discover that they had progressed to Level 4: I pointed out that because they had been arriving on time, behaving well, and trying to complete the classwork they were being awarded XP and those points were adding up each week.

It is important that the feedback system of a multiplayer classroom is as prompt as possible (Sheldon, 2012) so I updated each student profile after the lesson so when they next logged into their profiles they would see the results of their efforts that day.

The ‘threat’ of losing HP worked well as a deterrent when students were being talkative or disruptive in class, and if students persisted they usually quietened down once I told them they would not receive 100XP for good behaviour. In week12 I told a student he was close to ‘death’ and he stayed focused and behaved well. The following week I heard some students telling him, ‘Don’t lose HP as the whole team will lose 20HP’.

When students arrived late they would often ask, “Do we lose any XP?” They seemed to accept losing HP and not receiving XP for arriving on time – this seemed fair to them – but they did not want to lose the XP they had already earned; they accepted their ‘punishment’ however they wanted to know that they were not regressing in the game. Not deducting XP was another design feature that I adopted from Sheldon’s (2012:263) multiplayer classroom.

Students from the MG would sometimes come to the computer room during the break to check their profile. I was surprised that certain students who seldom used to take an interest in ICT seemed interested in XP; for example, during week3 a student from MG2 came to ask if he was still in first place for XP level; four weeks later he surprised me again when during change of lesson he came into my room to ask, ‘Am I still first?’ When I told him that since he had missed a few lessons and the test he was no longer first, he asked if he could do the test during the break.

Players want to be challenged, losing interest in easy games, (Malone, 1980, 1982; Greenfield 1984; Gee, 2007; Chatfield, 2010) and challenges should make players feel rewarded for doing their best (Gee, 2007; Whitton, 2010; McGonigal, 2011). I noticed that the students were not using the powers which were available, as since their HP was regenerating each lesson they had no need; subsequently, as HP levels were not running out, the ‘doom die’ was not being used. So midway through the study I stopped the HP ‘regenerating’ each lesson, to encourage students to use their ‘powers’. The majority of students seemed pleased to hear that instead of their HP automatically regenerating they would need to get a medic’s assistance, although a few who were low on HP did not seem as enthusiastic. This point was also raised in the interviews: both interview groups said they did not like the ‘doom die’ and HP; Pirlo believed that HP were not tough enough, suggesting that more HP should be lost for bad behaviour “to raise the risk”. As well as tougher HP penalties, two interviewees suggested that students be given less HP to begin with, creating more of an incentive not to break rules.

Powers

During my explanation of the Multiplayer Classroom, MG2 responded positively to the idea of protecting each other with ‘powers’ and as the weeks progressed, I witnessed more instances of students helping each other; this continued throughout the study. The questionnaires revealed that the powers were popular (Table 6.3 and 6.4). There were some discussions about which powers to buy in order to help each other; in week8 I heard a student tell his teammate he was going to ‘take a hit’ for him to save him 10HP.

Stopping the HP automatically regenerating raised the interest in students ‘purchasing’ powers; regenerating the HP level each lesson seemed to eliminate the element of risk and danger one would expect in a game and also made the medic’s powers redundant.

During the interviews, Zidane suggested creating a power where a player could take HP from another player. He explained:

Pirlo: You’d give it to a trooper and it would be an attack power […] Like that they’d be more team against team.

They continued to discuss how it could work. Delpiero then said that the Troopers’ and Agents’ powers are too similar, so an attack power would be good.

Badges

Badges (Figure 6.3) were awarded for good work, completing tasks, and other positive actions; for example, in week4 two students from MG2 both gave me a faulty pen drive to exhibit in class so I gave them a ‘donator badge’ and 100XP. In week6 a student from MG1 asked a good question regarding selecting non-continuous cells in a table which I incorporated into the lesson; I gave him a badge for his ingenuity. I also awarded gold, silver and bronze badges to those who came first, second and third in each test we did; in week5 the recipients of the badges were boasting about their awards. The students acknowledged the effort of creating the badges for them and seemed appreciative. The results from the questionnaire indicate that the badges were popular (Table 6.5 and 6.6)

Figure 6.3 – A selection of Badges

Role playing

Imaginative play can give more meaning to ordinary tasks, and there is a link between role playing and positive classroom functioning (Grimes & Feenberg, 2009; Fehr & Russ, 2013). Fantasy, as well as curiosity and challenge, were identified by Malone (1980, 1982) as key elements to encourage engagement with learning. The role playing added an element of fantasy and I witnessed a positive change in students’ behaviour; as well as intra-team support and cooperation, there were occasions when students would help the opposing team, for example, in week12, Team B did not push their chairs under their desks, so Hercules from Team A started arranging them. At this point Superman (also from Team A) said, “Don’t arrange their chairs, they’re the enemy – go see you in a real war!” to which Hercules replied, “You should know better as, like me, you’re a medic, and medics always help people”. The role of ‘medic’ also had an interesting effect on a student in MG1: at the start of the study, this student asked not to be assigned the role of medic as he was scared of blood; I said the ‘blood’ would be virtual but he insisted that just the thought of being a medic would make him nervous.

The interviewees in MG1 suggested that students change roles each term so that everyone would play each role; this led to an interesting discussion about problems with changing roles and possible solutions. One problem was that if you bought powers for a Trooper you would not be able to use them if you changed role: a suggested solution was a ‘refund’ on powers. It was good to see the students engaging enthusiastically in this discussion, offering suggestions for improvements and thinking through the implications of these changes.

Although the element of fantasy has the potential to create an intrinsically motivating learning environment, if the fantasies employed do not appeal to the target audience they may have a detrimental effect on the learning environment (Malone, 1981). Fortunately, I had asked my students in the previous scholastic year which games they preferred and this year ‘First Person Shooters’ were still popular.

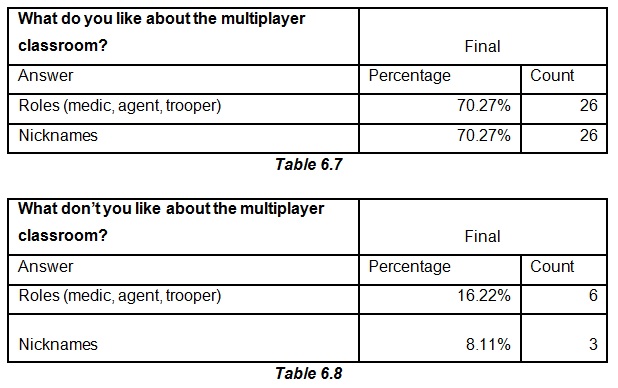

An interesting narrative can aid immersion and engagement into the game-world (Whitton, 2010). Although the students seemed to enjoy the narrative, and found it humorous that Comino was the subject, I think that if I had integrated the tasks with the narrative it might have engaged students more and further aided immersion; having said that, the students seemed to like the roles and the option of choosing a nickname (Table 6.7 and 6.8).

Random event

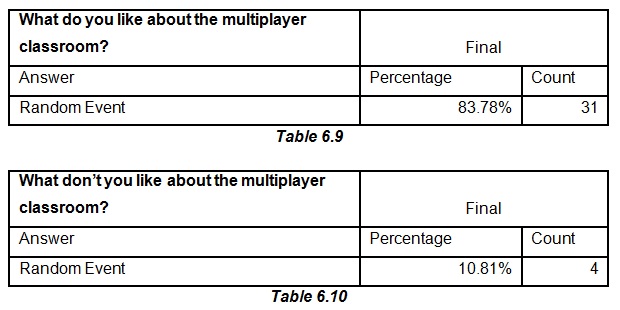

Curiosity keeps players from losing interest in games and can intrinsically motivate learners (Malone, 1980, 1982; Hong et al., 2009; Whitton, 2010; Sheldon, 2012). All interviewees said they liked the Random Event[1]Visit the Random Event page used.; one said it was more interesting and exciting coming to class as you did not know if the event was going to be positive or negative. The random event was popular in the MG (Table 6.9 and 6.10) and produced some positive results. Firstly, it generated some interest and enthusiasm; on many occasions students would remind me not to forget to spin the wheel. I was surprised that most students knew which events were available and every lesson there were discussions about which one they hoped would come up. In week9 an event came up for the second time and all the students, barring one, insisted that it was a repeat; I had to check my records, but the majority were correct.

It also added an element of competition, rousing some lively ‘trash talk’ and banter; for example, when Ironman won DJ for the Day, Penguin told him, ‘You’re still not going to beat my XP level!’ There were also out-bursts of joy and satisfaction, especially with The Pixar Challenge and DJ for a Day events. The positive social feedback associated with games can make individual success more rewarding (Gee, 2007; McGonigal, 2011); as well as some ‘trash talk’ amongst students, there were words of encouragement to spur on fellow teammates, particularly on timed activities. The winners of the random event challenges were visibly pleased with their success; as Malone (1980) states, being successful in any challenging activity can make a person feel better about themselves. During week14, a quiet student in MG1 was beaming with happiness when he correctly named three Pixar films earning him the XP. MG2 were equally as enthusiastic about The Pixar Challenge; when it came up on the spinner during week1, all hands went up to shouts of, ‘Ask me, I know!’ Penguin was extremely happy to win since he had lost 50XP for being late; he reminded me three times during the lesson not to forget to add the XP to his profile.

Whitton (2010) and McGonigal (2011) warn that in educational settings competition should be used with caution since competitive games can trigger negative emotions. While students who answered incorrectly to a random event challenge took the failure in good humour, there were a few occasions when students protested about a negative random event; the worst was for ‘Game Master Punishment[2]If a player loses HP that lesson, everyone has to copy a text or lose HP: 2 students arrived late that lesson.’ during MG2’s lesson in week9. It took a while to calm the situation; I told them that I did not want to waste time so if they preferred I could revert back to ‘normal’ lessons again: all said they wanted to continue, so I reminded them that agreeing to participate meant accepting that negative events might come up on the spinner. When ‘Earthquake – all students lose 15HP’ came up in MG1’s lesson and ‘Attack on Agents – all agents lose 20HP’ in MG2’s lesson, both complained due to the technicality that the word ‘ALL’ is used, arguing that absent students should also lose HP. However I told them that since only students present in class would benefit from positive events it was only fair that negatives only affect those present: they all agreed this was fair. I was pleased that they were taking an active part in the Random Event, and discussing and engaging with the rules.

Starting the lesson with the Random Event was beneficial as when the sound of the wheel spinning came on the speakers the students’ attention was focused on the board: the random event had quickly come to mean ‘It’s time to pay attention’ without the need for me to settle them down. On occasions when I did not start with the Random Event it took longer for them to settle.

Doom die

At the start of the study, MG2 seemed concerned about the HP and in particular the ‘doom die’. The data from the questionnaires (Table 6.11 and 6.12) and the interview groups also indicate that the ‘doom die’ was not popular; however, it emerged from the interviews that some students thought the ‘doom die’ was not used enough, and this was why it was unpopular. One suggestion from Buffon was to “give us less HP so that we use the ‘doom die’ more.”

The only game ‘death’ was in week9: Greengoblin rolled the die at the beginning of the lesson, and rolled a 3 which meant a break detention; however, he did not attend. I warned him that if he did not abide by the rules he would be removed from ‘the game’; he seemed upset about this and said he was willing to take a formal detention[3]This would go on his permanent record., as long as he could stay in the game. He said he had honestly forgotten to attend, so I gave him another chance with another break detention (which he attended) and he received 50HP.

The suggestion from one interviewee to introduce a power that would allow players to plunder HP from another player had a drawback; an interviewee pointed out that since one of the punishments on the die is an official detention it would be unfair if a student received this punishment because his HP had been ‘plundered’. I suggested that the ‘doom die’ could be changed if that power was introduced: they agreed and discussed what could be done – one suggestion was to have two dice, one for bad behaviour consequences, and the other for HP ‘attacks’.

Profiles, website and levelling up

One interviewee said that he liked the look of the website, describing it as user friendly. The others agreed it was quite organised and easy to find things. The questionnaire results indicate that the website was popular (Table 6.13 and 6.14)

The interviewees from MG1 all said they visited the website and said there was nothing they disliked about it. Zidane said:

He said he also liked to see how much HP was left and who was going to ‘die’. Another interviewee said he checks his profile but not every day, and two said they check but not very often. Delpiero commented:

It was at this point during the interview that Zidane suggested creating a power where HP could be taken from another student, as an incentive for students to check their profile to know who to attack. The others liked this idea.

The interviewees from MG2 had mixed feelings about the website and their profiles. Ironman said he never checked his profile:

Wolverine: Yes, one password would’ve been enough – why the heck did you do two?

Superman: There’s no real problem if you use them often – I’ve learnt mine by heart. I like the fact the website’s accessible on tablet. A lot of websites only open on laptops, but this one even opened on my tablet with no problems.[ Wolverine agreed with this] I go on the website to check how much XP I have.

Table 6.15 shows approximately how often the MG checked their profiles.

It was quite time consuming updating all the profiles; however, as the weeks progressed I got quicker at it. A programmer could possibly create an online management system where all the XP/HP data is centralised, making it easier to update profiles.

Teamwork

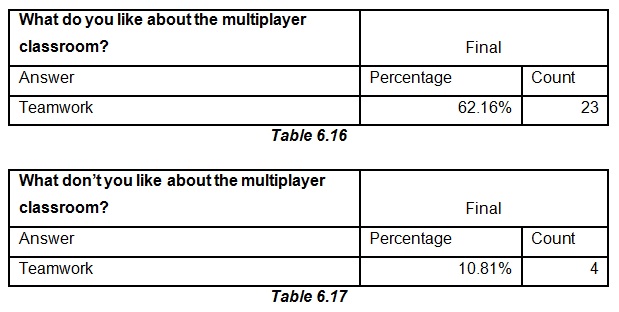

Community is a central aspect of MMORPGs (Humphreys, 2005; Ang & Zaphiris, 2010; Curry, 2010; Peterson, 2010; McGonigal, 2011; Sheldon, 2012) and a sense of belonging to a community can make students feel good and foster a positive atmosphere in class. Both MGs responded positively to the teamwork aspect of the multiplayer classroom, and this was echoed in the interviews. When asked what they liked about the multiplayer classroom, Zidane (MG1) said “I like the teams because the teams were random.” Ironman (MG2) said he liked the teams because “it enforces the fact that because we’re in a class, we’re a team” to which Superman added, “In a team you belong” which Magneto agreed with. Overall, the MG worked well together and appeared to enjoy the teamwork (Table 6.16 and 6.17), engaging with the tasks and seeming eager to complete as much as possible.

Valuable skills can arise from team games, such as leadership skills (Abernethy, 1974; Gee, 2003; Peterson, 2010) and this was noted among some students with regard to allocating work during lessons, telling teammates to arrange their uniforms and reminding them to tidy their workstations.

The interviewees from MG1 said they “definitely” (Buffon) felt more motivated to help their classmates this year. From the beginning of the study MG1 were enthusiastic about working in teams, though they sometimes forgot to sit together or had to be reminded that they could help any team member, not just the person next to them; however, by week5 this occurred more naturally, to the point where even if a friend sat next to them they would tell him to sit with his team. I also regularly saw students getting out of their chair to help another teammate.

The interviewees from MG2 unanimously agreed that they wanted to be more involved in lessons this year because they were in teams but complained that they did not always feel like part of a team during the theoretical part of the lesson as they did not always sit in teams. They agreed that they should sit in their teams for the duration of the whole lesson (during the explanation as well as the practical part of the lesson). Ironman pointed out that as the class is arranged in three rows “there’s already the ‘territory’ there” and suggested that HP be deducted if someone sits in the wrong ‘area’, saying, “You have to put your mind there; you came in for the game, you came in for a challenge.”

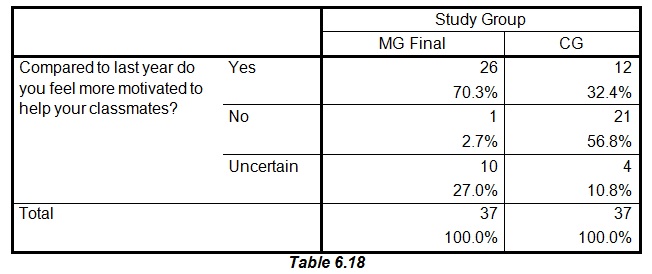

There was a significant difference (X2(2,N=74)=25.911, s) between the responses from the CG and MG (Table 6.18 and Figure 6.4) with regard to feeling more/less motivated to help their classmates. The majority of MG said that they felt more motivated to help this year, whereas over half of the CG said they did not feel more motivated to help their classmates.

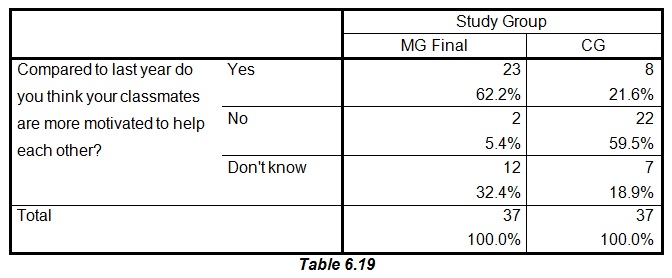

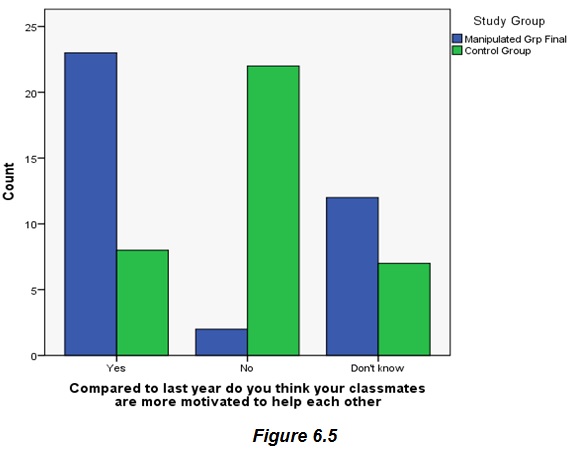

There was also a significant difference (X2(2,N=74)=25.241, s) between the CG and MG responses about whether they thought their classmates were more motivated to help each other: 23 from the MG answered ‘yes’ they thought their classmates were more motivated, while 22 from the CG answered ‘no’ (Table 6.19 and Figure 6.5).

A comment made by Zidane correlates with the theory that games can help to build social bonds (Gee, 2007; McGonigal, 2011) and that working in teams encouraged him to get to know another member of the class.

Bluemink et al. (2010) warn that collaboration may not always be successful and can lead to negative feelings. There was a negative observation from two interviewees from MG1 who said that sometimes some students let their partner do most of the work:

Pirlo : Like myself, Pereyra is careless – not that he doesn’t want to do or know how to do the work – but say if a table is 7 by 8, he’ll do it 8 by 7, or if he’s copying something, he’ll spell it right but will not focus on capital letters.

Unfortunately, this can sometimes occur during ‘normal’ lessons, so even in a multiplayer classroom setting teachers need to be wary of this. Despite this, however, all interviewees said that they liked the teams.

In digital games multiplayer modes encourage collaboration and the chance to learn with and from others (Griffiths & Davies, 2002; Whitton, 2010; McGonigal, 2011). Teamwork can reduce the pressure on individuals by focusing attention on a group effort (Whitton, 2010; Sheldon, 2012). I observed more students taking an active part in the multiplayer classroom compared to lessons last year. Interviewees also said that they felt less pressure than in previous years, and because of the teams they felt encouraged to keep trying, feeling less worried about asking questions and perhaps saying something wrong. Two students from MG1 said:

Pirlo: If you have a question, even in the activity, you ask.

They agreed that if they found something difficult they would not want to give up, they would want to continue trying “because you gain from it if you persevere” (Delpiero). MG2 voiced similar opinions; Ironman said:

They all agreed with this, and Superman added that having teams was better than just working in pairs, “the fact there’s more members in a team, you have more people to ask, more people to help you, so it’s easier.”

Failure is not negative in games since players learn by making mistakes (Gee, 2007; McGonigal, 2011; Sheldon, 2012). The interviewees from MG2 all agreed that they worried less about making mistakes when working as a team. Ironman said that in ‘normal’ lessons he would not “take a risk” but in a team he found “more courage to participate. If you make a mistake maybe there’ll be someone who will notice and correct it for you.” The others agreed, and Wolverine added, “You make fewer mistakes in a team.”

The ‘safe surroundings’ created by the game-world frees learners from the fear of failing, enabling active and critical learning to occur (Eglesz et al., 2005; Gee, 2007; Whitton, 2010, 2011). I observed more active participation during lessons with the MG, and students seemed more eager to answer, which was encouraging to witness. However, from MG1, Pirlo said he was not sure if he felt less concerned than last year or if he felt exactly the same, and while Delpiero had said that he did not worry about asking questions and perhaps saying something ‘wrong’, he said that he did feel more worried about making mistakes when working on the PC this year as he did not want to let his teammate down:

Collaborative activities and creating a class community can help nurture a sense of social obligation and encourage positive participation out of respect for fellow teammates (Curry, 2010); however, for Delpiero the sense of obligation added some negative pressure when working on the PC as he wanted to do the task well and not let his teammate down.

The CG worked in pairs and generally co-operated, although they sometimes complained about working together; in week7 CG1 complained about sharing PCs, so I suggested working as a team but they said they did not want to. In the MG there appeared to be a reduction in the number of arguments that would normally occur in class, particularly with sharing a computer and there was an increase in the number of students helping each other in their teams. There were some arguments in MG2 in week8, but after reminding them that they should work together in teams, they stopped.

Some of the learners in Sheldon’s (2012) multiplayer classroom participated well in the lessons but were frequently absent and did not study enough; Sheldon likened them to “players encountered in any MMO, wearing armour too fragile and wielding weapons too blunted, to survive” (2012:39). There was a problem with absenteeism in MG2 with five students who were regularly absent[4] The SMT knew about these cases and were updated when they were absent. which the interviewees said had affected their team; Superman (MG2) said, “If the others don’t come to school it’s a disadvantage”. This was unfortunate, as when these students did attend they took an active part in the lesson.

Footnotes

| ↑1 | Visit the Random Event page used. |

|---|---|

| ↑2 | If a player loses HP that lesson, everyone has to copy a text or lose HP: 2 students arrived late that lesson. |

| ↑3 | This would go on his permanent record. |

| ↑4 | The SMT knew about these cases and were updated when they were absent. |